Learning Advocacy: Building From What is Known to Unknown

By Cecile Lantican

May 8, 2012

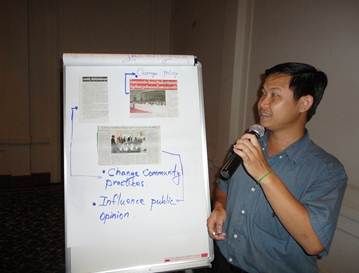

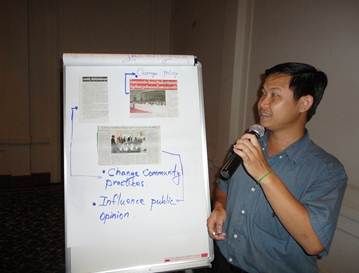

With the newspaper clippings, the participants organized their thoughts and began to identify examples of advocacy being applied to a public cause. For example, one participant explained the media plan by the government to advocate for immunization. With the newspaper clippings, the participants organized their thoughts and began to identify examples of advocacy being applied to a public cause. For example, one participant explained the media plan by the government to advocate for immunization.

In advocacy, much depends on enlisting the people who have the influence to make a difference (Handouts #4 and 5). The newspaper clippings showed them examples of who were the “influentials” in the government service and in their communities.

To help them understand more the qualities of “influentials” being discussed, I showed them the video of three important figures in Laos. I requested the video clips from Lao Star Television. The video contained footage of the Lao President, the Committee Party Administrator, and one governor.

The video enabled the participants to describe the characteristics and qualifications of influentials who could act and do something about issues they cared about.

The NOT ON OUR WATCH website was used maximally to demonstrate how to do an influential analysis and practical examples of messaging. Some participants used their mobile phones to get through the internet.

With the internet connection in the room, the participants and I explored together and discussed more examples of traditional and non-traditional outlets and channels. We explored the internet together – visited various advocacy websites and studied some examples.

The downside of this approach however was the fact that websites we visited were in English. English as a third or fourth language for most of our participants did take more time to read and comprehend the content. Nevertheless, I was confident that through the internet, learning was more interactive, evolving, and an experiential process.

The hot seat exercise put the participants to the test. Working in pairs, I asked them to work on an issue they think important in their province or community. One had to play the role of a community leader and one as the decision maker.

A woman who acted as a farmer federation leader presented to the town mayor the farmers' problem on irrigation. The farmers' rice production was low because of lack of water caused by closing of the national irrigation system by the provincial government.

A dialogue between the president of the student organization and a university President was played out.

The student leader advocated for the students’ concern of the growing number of students who smoke and litter in the campus which also created impact on the student’s “cleanliness and save the environment” campaign.

One MoAF staff, who served as the Manager of Information and in-charge of the library and knowledge management department of MOAF, demonstrated how to present to the Executive Director of Planning and Investment the problem about old communication equipment such as computers, internet connection, access to new publications and journals, and deteriorating services of her department.

At the closing of the training on the second day, one staff from the Faculty of Agriculture, Nabong Agricultural University volunteered to share her testimony about the training.

“I joined this training with no idea about advocacy. But I appreciated the learning process I experienced with my group. I am an educator myself. I find this kind of training very useful. I believe that this training entails greater costs to FHI 360 – but if we pass on the learning to others and the learning will be applied, then the costs would be lesser.”

Dr. Somphan, in his closing remarks, stressed, “Advocacy skills can be applied in any issues that you are confronted with in your respective departments. I enjoin you to share this knowledge and skill with your colleagues and start informing your stakeholders of what you are doing so that you can get their support.” Dr. Somphan, in his closing remarks, stressed, “Advocacy skills can be applied in any issues that you are confronted with in your respective departments. I enjoin you to share this knowledge and skill with your colleagues and start informing your stakeholders of what you are doing so that you can get their support.”

The shared learning with the participants was such a fulfilling experience. It could be “difficult” in the process yet effective because the motivation to learn was internally generated among the participants themselves.

MID-BCC Project is funded by USAID.

Photos by Cecile Lantican 2012 | FHI 360

Back to top

< PreviousBlog Home >

|

With the newspaper clippings, the participants organized their thoughts and began to identify examples of advocacy being applied to a public cause. For example, one participant explained the media plan by the government to advocate for immunization.

With the newspaper clippings, the participants organized their thoughts and began to identify examples of advocacy being applied to a public cause. For example, one participant explained the media plan by the government to advocate for immunization.

Dr. Somphan, in his closing remarks, stressed, “Advocacy skills can be applied in any issues that you are confronted with in your respective departments. I enjoin you to share this knowledge and skill with your colleagues and start informing your stakeholders of what you are doing so that you can get their support.”

Dr. Somphan, in his closing remarks, stressed, “Advocacy skills can be applied in any issues that you are confronted with in your respective departments. I enjoin you to share this knowledge and skill with your colleagues and start informing your stakeholders of what you are doing so that you can get their support.”